Spears

| Spears |

|---|

|

More Weapons pages

|

A spear is a spear whether it is of the |

|

R.Ewart Oakeshott, The Archaeology of Weapons, 1960 |

If one ignores Oakeshott’s [OAKESHOTT 1960] rather short and glib analysis of spears in his seminal work ‘The Archaeology of Weapons’ then you quickly realise that spears follow fashion changes by time and region in much the same way as swords. Although not as glamorous as the sword, the spear was in every sense the definitive weapon of the Viking Age and used as the primary weapon of combat by almost every warrior. Decorated spearheads inlaid with precious metals prove that in the Viking Age spears were not seen as the poor man’s choice and one has only to look at the representations of warriors from the illuminated manuscripts of the era to quickly come to the conclusion that the use of the spear was ubiquitous. Many of the Anglo-Saxon phrases used to describe both battle and warrior help to underline the importance of the spear.

Art

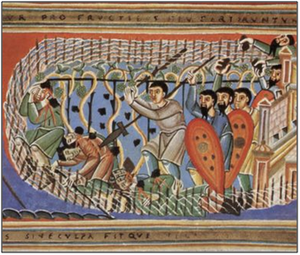

Numerous Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian sources depict the use of the spear being used one handed in an overarm style.

Literature

- Caedmon, æsc-plega, “Spear-bearer” is applied to a soldier. [HEWITT 1855]:P.28

- History of Judith, æsc-plega, “play of spears” used as a term for battle [HEWITT 1855]:P.28

- Codex Extoniensis, æsc-stede, “a field of battle” [HEWITT 1855]:P.28

- Beowolf, Eald æsc-wiga, “some old spear warrior” [HEWITT 1855]:P.28

Archaeology

--

Discussion

Manuscript drawings tend to be stylised and often copied older templates. Spears are depicted often and most warriors are seen to be carrying them. Unfortunately the spearheads are usually shown as a simple arrow shape which bears no resemblance to the actual spearheads found in archaeology.

We do have a number of depictions of spears from stone sculptures in Britain. The carving of Christian stone crosses became popular in northern England in the 10th and 11th centuries [RICHARDS 2004]:P.214.

Paul Hill points out that the term æsc is only used to refer to large two-handed, long bladed weapons used by a high status warrior [HILL 2004]:p.65. He then goes on to argue that the term geir was more commonly used.

Spearheads

Art

--

Literature

--

Archaeology

- England. So far I have identified 45 spearhead finds from England. 20 are of type K/M or M. 7 others are of winged form.

- Wales. 2 finds [REDKNAP 2000]:p.53-54

- Iceland. 81 spearheads have been found dating from the Viking Age. They have been found in 56 graves and 22 spearheads have been registered as stray finds. 40 spearheads belong to type K, 3 to type G, 2 to type H, 3 to type I and 1 to type E. The remainder are probably of local manufacture and do not sit easily within Petersen’s typology.[ANDROSHCHUK & TRAUSTADOTTIR 2004]

Discussion

Most spearhead finds dated from 800AD to 1100AD in Britain are single discoveries often from rivers and are dated by their form against Petersen’s typology.

We do however have a few graves in Scotland, the Isle of Man and northern England. Unfortunately most of these were excavated in the 19th Century with only basic notes about the burials being recorded. To make things even worse many of the spearheads from this era have ended up in private collections or have become ‘lost’. Haakon Shetelig [BJORN & SHETELIG 1940] has helped us here by compiling a series of books of Viking Age finds from England and Scotland. These books list all of the known finds up to 1940 including some that are now lost.

Categorising spears, javelins and arrows

The following size categories are extremely arboratory

Arrow

Javelin

One-Handed Spear

Two-Handed Spear

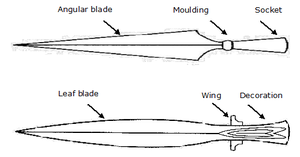

Spearhead with open or closed sockets

Wheeler used the spear socket to determine the origin of the spearhead. He classed all spears with a split ‘open’ socket as being English in manufacture and those with overlapped ‘closed’ socket as Scandinavian [WHEELER 1935]:p.170. This convention has continued in use to the present day.

Spearhead manufacture

Pollington states that there is a marked increase in standardisation of Spear heads forms compared to the earlier Anglo-Saxon pagan period (covered by Swanton). He makes the case for this being due to the Alfredian burh system and the centralisation of manufacture away from the traditional labour-intensive smithing on a village or estate scale [POLLINGTON 2006]:p.137

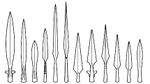

Spearhead typology

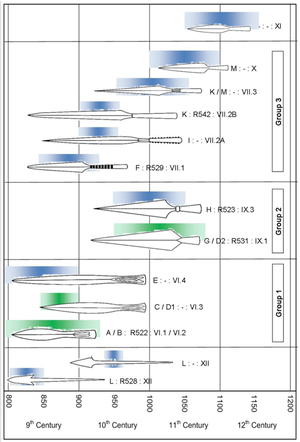

Petersen created the first and still the most used typology of spearheads for the Viking Age in 1919 [PETERSEN 1919]. His typology is based on finds from Norway and includes some types that are rare or nonexistent in Britain. It must be remembered that Petersen was working on dates derived from associated items found along with his spear-heads in Norwegian pagan burials and that he often commented on the difficulty of precisely dating a specific burial find.

Thålin working on Swedish finds radically simplified Pertersen’s typology into 3 groups based on the method of manufacture. Thålin’s groups are refered to in Graham-Campbell [GRAHAM-CAMPBELL 1980]:P.67, P.72 and explained in Fuglesang [FUGLESANG 1980]:P.137.

Swanton [SWANTON 1973] presents us with an in depth analysis of spearheads found in pagan Saxon graves in England. Unfortunately this only takes us up to around the time of the Christian conversion, about 700AD. After this our burial record in England disappears with the Christian’s practice of burying their dead with no grave goods.

Solberg re-evaluated Petersen’s work as his 1985 Phd thesis, again working from Norwegian finds. Solberg’s work is discussed in Halpin [HALPIN 2008].

Two settlements from Europe can be used to help corroborate Petersen’s typological dating, Iceland and the town of Birka in Sweden. Both have clear datable horizons that help us to place spearheads into clearly dated periods.

Iceland was probably settled c.874AD and out of the 81 spearheads dated to the Viking Age from Iceland only one falls into Thalin’s group 1. All of the others are from his groups 2 and 3 (K x40, G x3, H x2, I x2, E x1, Unclassified x33) [ANDROSHCHUK & TRAUSTADOTTIR 2004]:P.6.

The settlement at Birka came to an end around c.960AD. No spearheads of K/M or M types were found there, which would help confirm a late dating for these sometimes decorated spearheads. [FUGLESANG 1980]:P.33

Both of these settlement horizons help confirm Petersen’s original typological dating.

Leaf shaped heads

Thålin Group 1

Leaf shaped heads, Petersen types A(B), C(D1) and E, seem to go out of fashion by 950AD [PETERSEN 1919]. Other people have suggested that a few leaf shaped heads may have continued throughout the period [Citation Needed].

Angular shaped heads with short sockets

Thålin Group 2

Group 2 consists of Petersen types D:2, G and H. They are all types with edge shoulders placed low on the blade and a short conical socket with marked narrowing below the blade.

Fuglesang includes the winged spears of Petersens type D2 in with this group as he removed wings as a determinant of typology making Petersens D2 and G types the same. See the section on ‘Winged Spears’ for examples of D2 style spear heads.

It has also been suggested by Fuglesang and Petersen that type G spearheads without wings may be of eastern origin with the majority of finds coming from Sweden and Finland. A few decorated type G spears have been found with Urnes style decoration.

Angular spearheads with long sockets

Thålin Group 3

Group 3 consists of Petersen types F, I, K & M. They are all types with a narrow blade which is often shouldered and a socket that is long, narrow and conical.

Fuglesang has studied the K & M types of spearhead that are decorated in Ringerike designs. Due to difficulty in determining the exact typology of many of these spearheads she has introduced a new K/M type that falls between those of Petersens K and M.

F – 30cm to 50-60cm, 50-60cm being typical.

Javelins or darts

Javelins, sometimes referred to as ‘darts’, are small spears designed for throwing although it is likely that they were also used as thrusting weapons in the same manner as spears.

Angons

Petersen type ‘L’ spearheads

A 3 foot long metal shaft with twin barbs mounted on a wooden shaft.

A Frankish weapon used in a similar way to the Roman pilum and in fashion between the 5th to mid 8th century. It was designed to be thrown at the enemy’s shield. The iron shaft would hen bend and the weight of the angon would pull the enemy’s shield down. [THOMPSON 2004]:p.52-53.

A similar weapon is Petersen’s type L spear. The primary difference is that whereas the Angon was socketed, Petersen’s Norwegian spears were tanged. Two types are described. The earlier barbed form is more numerous and dated to the first half of the C9th. Petersen could only cite 2 examples of the later type which dates to the mid C10th. This form’s head is more triangular in shape and is not barbed. [PETERSEN 1919]

Spearheads with attached wings or lugs

Lugged spear-heads of this kind, sometimes referred to as the Carolingian type, are common from Viking contexts from the 9th century onwards, both in Scandinavia and England, but the most recent studies cautiously point out that it can no longer be regarded as exclusively Scandinavian in character.

|

Though Petersen used the lugs as diagnostic features for his typology of spears, recent scholars have very properly challenged the notion that they serve as chronological or stylistic indicators. Because the lugs have a function in preventing too deep a penetration of the blade, this type of spear was used primarily as a hunting weapon, since with it the animal could be more easily held at bay. So successful was it that it survived in use until the end of the Middle Ages. That it was so employed is demonstrated by the 10th-century cross Middleton A, near Pickering, which depicts a stag hunt with the huntsman wielding a lugged spear. Signe Horn Fuglesang's [FUGLESANG 1980]:P.136 discussion of such sockets has convincingly removed the lug as a typological factor, and as a chronological criterion too. |

| [LANG 1981] |

Often referred to as Carolingian spearheads as originally they were classed as C9th Carolingian imports [GRAHAM-CAMPBELL 1980]:p.72. This date line has now been extended as there are a number of later period depictions such as on a German manuscript (Codex Aureus Epternacensis fol.78) dated to 1040AD. In this manuscript the spear is seen being used single handed over arm in conjunction with a kite shield. It may even have survived in use until the middle ages [LANG 1981].

It has been suggested winged spears may have been hunting spears [FUGLESANG 1980]. As an example she uses the C10th Middleton Cross A stone, which has been interpreted as a hunting scene.

The winged spear can be seen in a few manuscripts illustrations and stone carvings.

... with backswept wings

Two examples of spears with backswept wings has been found in England. This type of spearhead could be considered to be an eastern (Finish) type except for the find from York and another from the British Museum [FUGLESANG 1980]:Fig.3 [LANG 1981] [KENDRICK 1949]:Pl.LXIX.

Decorated spearheads

Some of the K, K/M and M types of spearheads are decorated in Ringerike style around the join between the blade and the socket. A group of 24 such ornamented spear-heads of types K, K/M, and M has been discussed by Fuglesang [FUGLESANG 1980]. Only one of these was found in Britain [WHEELER 1927]:p.21 Fig.5. Except for another from Belgium they seem to concentrate in Sweden although as Fuglesang correctly points out, not enough finds have been made to make any firm statements regards regional origins.

Magi-Lougas has devided spearhead decoration into 3 types [MAGI-LOUGAS 1994]

Type I – Silver Decoration

characterised by the use of different metals, or metals of different colours, to form the ornament

E-, I- K- and K-type spearheads, but also in some cases to G-type

Type II – Ringerike Style

1000 – 1060AD

Type III – Runic Style (Urnes)

1025 – 1100AD

Type II Ringerike decoration on a type K spearhead [WHEELER 1927]:P.21

Spear butts

Also known as a shoe or ferrule. It appears that generally spear butts were not used during the Viking period. An exception to this is those found in Ireland.

Art

--

Literature

--

Archaeology

- Ireland, Kilmaniham-Islandbridge. [GRAHAM-CAMPBELL 1989]:p.25

Discussion

--

Spear shafts

Woods used

Identification of wood from spears in the Baltic region shows that shafts were made of ash, elm or oak. These kinds of woods were used because of their straightness of grain, stiffness, hardness, strength, moderate weight, flexibility, and capacity for being smooth in use [ANDROSHCHUK and TRAUSTADOTTIR 2004]. Spear shafts were likely to be no thicker than 3cm in diameter. [HALPIN 2008]

Attaching the spearhead

A number of methods seem to have been used to secure the spearhead to the wooden shaft.

Art

- Anglo-Saxon manuscripts depict spear heads with one or more lines through the socket. These have been interpreted as possible rivets.Template:Citation needed

Literature

--

Archaeology

- Dublin, 66% of the spearheads from Dublin had rivet holes with the hole size usually being between 2 to 3 mm in diameter [HALPIN 2008]:p.134.

- Isle of Man, Balladoyne. A type K spearhead retained traces of a fine linen fabric that had been wrapped twice around the point of the wooden shaft [BJORN & SHETELIG 1940]:p.26.

- Hedeby, Denmark (Germany). A type E spearhead found in the harbour complete with 1m of remaining ash shaft. The shaft is 25mm in diamter and slightly oval in cross section. The shaft is only held on by the 71mm of wood inserted into the spear socket. No rivets or other forms of attachment have been found. [WESTPHAL 2006]:p.61

Discussion

Riveting, pinning and gluing were probably the most common.

Painted Spear Shafts

Spear shafts that are painted or stained for decorative effect

Art

Anglo-Saxon manuscripts only show spear shafts as a thin black line. Some Western European manuscripts depict thicker shafts filled in a single colour.

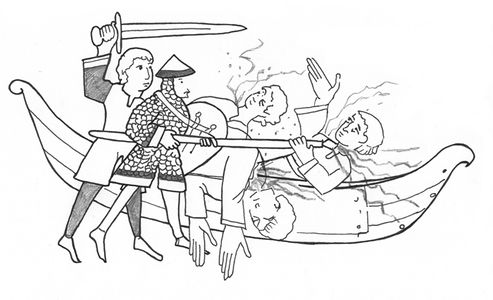

- Life of St Aubin, Angers Abbey c.1100AD

Literature

--

Archaeology

--

Discussion

Currently we have no evidence for spear shafts being painted in more than one colour from the Viking Age.

Carved Spear Shafts

Spear shafts that have been carved for decorative effect

Art

--

Literature

--

Archaeology

--

Discussion

--

Using spears one-handed with a center gripped shield

Art

Numerous Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian sources depict the use of the spear being used one handed in an over arm style.

Literature

--

Archaeology

--

Discussion

Probably the most common weapon in use during the Viking Age.

Using a spear two-handed with a slung shield

Art

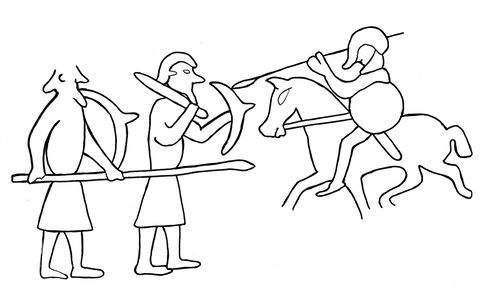

So far all the images of men using a spear two-handed with a slung shield show them against either animals, ships or castles.

- Scotland, Aberlemo stone. c.700-850. Depicts a warrior attacking a mounted warrior.

- France, Saint-Omer. c.1000-1025. Depicts a man hunting a boar. (New York, Pierpont Morgan, MS.333 fol.1)

- Germany. St Gallen?. c.1125-1150. Depicts a warrior attacking a ship. (St Gallen, Cod. Sang, 863)

- England, Canterbury. Stained glass window. c.1190. Depicts a warrior attacking a castle.

Literature

--

Archaeology

--

Discussion

Using a spear in combat two-handed and with a slung shield evolved in the 1980’s as a way of winning re-enactment battles [SIDDORN 2005]. Using a spear in this fashion has one huge obvious disadvantage, you cannot defend your head with your shield! Having said this I do believe that some of the large headed winged spears could have possibly been used two-handed, as both hunting spears and combat spears.

To the best of my knowledge we have no written sources that describe this form of warfare. This is not surprising, however, as most of the writings that we have are either short, factual chronicles or allegorical poems. From archaeology we have hundreds of large spearheads. On the whole these still have thin sockets, usually less than 25mm (1”) in diameter, and so would be unsuitable for the stout spear shafts that you would expect to see associated with a two-handed weapon. Another argument against their use in this manner are the manuscript images clearly showing these large spear heads being used single-handed, such as the Codex Aureus Epternacensis illustrated in AD c.1040.

We do however have numerous images of warriors using spears two-handed. Just not in association with a shield. This is what you’d expect as anyone armed with just a spear would automatically use it with both hands.

This leaves us with the 4 images shown here. The earliest is from a Pictish picture stone depicting a battle and dating to somewhere between AD 700 to 850. The second is from a European manuscript made in Switzerland dating to AD 1125-1150. The third is from a stained glass window in Canterbury Cathedral and dating to AD 1190.

All of these images depict warriors fighting against non-infantry.

Byzantine and Carolingian armies were known to use two-handed spears, or pikes, for use against mounted warriors. But for England we have scarce evidence for the use of mounted warriors prior to the Norman Conquest. If two-handed spears were in common use in AD 1066 we would expect to see them depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry and being used against the Norman cavalry. Instead we see Dane-axe wielding warriors fulfilling this role. It appears that England and Scandinavia chose a different way to deal with cavalry than adopting the two-handed spear.

It seems then that the main use for stout two-handed spears in England was probably for use in hunting, the pursuit of the rich. This is not to say that they could not have been used on the battlefield as they would have made very effective weapons.

References

- Weapons

- 2 Stars

- Androshchuk & Traustadottir 2004

- Bjorn & Shetelig 1940

- Fuglesang 1980

- Graham-Campbell 1980

- Graham-Campbell 1989

- Halpin 2008

- Hewitt 1855

- Hill 2004

- Kendrick 1949

- Lang 1981

- Magi-Lougas 1994

- Oakeshott 1960

- Petersen 1919

- Pollington 2006

- Redknap 2000

- Richards 2004

- Siddorn 2005

- Swanton 1973

- Thompson 2004

- Westphal 2006

- Wheeler 1927

- Wheeler 1935